Development

Download Development (2,661 KB)

Achieving Greater Development Impact: Collaborating across the System

The next decade is critical.

We need substantially greater impact in helping countries achieve sustainable development and inclusive growth, and in managing the growing pressures in the global commons. The current pace of change will not get us there.

We need bolder reforms to harness complementarities and synergies in the development system:

-

Refocus IFIs’ efforts to help countries strengthen governance capacity and human capital (Proposal 1), as the foundation for an attractive investment climate, job creation, and social stability.

-

Exploit the largely untapped potential for collaboration (Proposal 2, 3) among the IFIs as well as with development partners to maximize their contributions as a group, including by convergence around core standards.

-

Embark on system-wide insurance and diversification of risk (Proposal 4, 5), to create a large-scale asset class and mobilize significantly greater private sector participation.

-

Strengthen joint capacity (Proposal 6, 7, 8) to tackle the challenges of the commons.

We must also leverage more actively (Proposal 9) on the work of the non-official sector, including NGOs and philanthropies.

Bold and urgent reforms in development policies and financing are required to achieve the major step-up in growth, job opportunities and sustainability that the world needs in the next decade.

We must achieve significantly greater development impact in every continent. The road to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) must pass through Africa, in particular. It has great potential to contribute to global growth in the coming decades. But Africa also faces unprecedented poverty, demographic, jobs and environmental challenges (see Box 1). The consequences of failure will not be simply economic.

We must organize the world’s multilateral development capabilities and resources in a new way to address these challenges and achieve greater and more lasting development impact. The IFIs are uniquely positioned as multipliers of development – by supporting good policies, strengthening institutions, promoting innovation, taking programs to scale and mobilizing private sector investment.

There is much further potential to be unlocked by governing the system as a system rather than as individual institutions.

Given the critical need to attract much larger volumes of private risk capital, and in particular equity financing, we must maximize the IFIs’ unique ability to help reduce risk in order to draw in private investment by:

-

Helping countries to de-risk their whole investment environment (besides de-risking projects). The IFIs must collaborate to help countries take advantage of current best practices in governance and regulation.

-

Pioneering investments in lower income countries and states with features of fragility, in critical areas such as energy infrastructure, to reduce perceived risks and pave the way for private investments.

-

Mitigating risk through instruments such as first-loss guarantees, and co-investments to catalyze private investment.

-

Leveraging on the largely untapped potential to pool and diversify risks across the development finance system, so as to create new asset classes for private investors.

To achieve these objectives, IFI governance must place rigorous emphasis on additionality – ensuring that guarantees and concessional resources are deployed where they have the greatest catalytic role in attracting private capital and addressing market failures. Importantly, they must use their risk-mitigation tools to attract private investment to the least developed countries, in addition to the middle-income countries in which blended finance has been heavily concentrated so far.

Box 1: Africa’s Opportunities and Challenges

Africa has grown well over the past decade, expanding at over 4 percent on average. But there are major challenges ahead, and setbacks in some parts of the continent that need to be overcome.

The coming decades offer great opportunity. With strong reforms in governance, human capital, and the investment climate, an environment can be created that brings greater job opportunities for Africa’s burgeoning youth population and spurs sustainable and inclusive growth.

However, poverty and environmental challenges remain severe and could worsen without continuous reforms and investments to create jobs, and to pre-empt the implications of climate change for food security and the spread of diseases

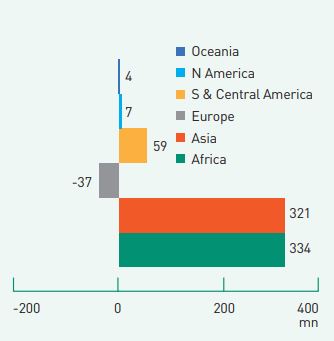

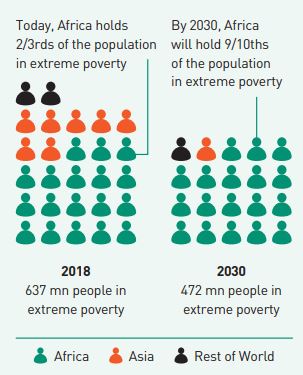

| Africa will see the largest increase in working age population from now to 2030. | By 2030, nine in ten of the world’s extreme poor are projected to be in Africa. |

| Growth in Working Age Population by 2030 | Global Population in Extreme Poverty - 2018 and 2030 |

Source: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017), UN; The 2017 Revision. Source: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017), UN; The 2017 Revision. |

Source: World Poverty Clock Source: World Poverty Clock |

The pace of growth in the young, working age population in Africa will be unprecedented in global history. It offers the possibility of a significant market for global goods and services, with Africa’s middle class expected to grow by 100 million.

However, at the current pace of economic growth, job creation will still be short of needs, which in turn implies a persistent difficulty in reducing extreme poverty. By 2030, nine in ten of the world’s poor are expected to be in Africa. A young population that is not gainfully employed could also become a source of instability

Growth in agriculture has tremendous potential, given Africa’s vast tracts of arable land. Its realization will depend on the adoption of improved techniques, commercialization, and better utilized water resources. There are also huge opportunities for digitalization of Africa’s economies and developing resource-based manufacturing to increase domestic value-added.

Mobilizing the private sector to support these goals will be critical. Thriving African economies, connected to global markets, can become a new engine of growth and will contribute to tackling the challenges of the global commons.

The scale and urgency of needs requires decisive, system-wide shifts. We believe significantly greater development impact can be achieved by:

-

Refocusing on supporting countries’ efforts to strengthen governance capacity and human capital, both critical tasks. Decades of experience in development have shown these to be the critical foundations for an attractive investment climate, job creation and economic dynamism.

-

Governance reform lasts only when it comes from within. But the IFIs, as trusted partners in the adoption of best practices and institutional innovations, have to work more closely together, and with countries’ other development partners, to support enduring reforms.

-

The IFIs must also support governments in ensuring the broadest base in human capital development: providing equality of opportunity for all, regardless of gender, ethnicity and social backgrounds.

-

-

Joining up IFIs’ operations, as well as with those of other development partners, to enhance development impact:

-

Build effective country platforms to mobilize all development partners to unlock investments, and maximize their contributions as a group, including by convergence around core standards.

-

The platforms must be owned by governments, encourage competition, and retain the government’s flexibility to engage with the most suitable partners. But transparency within the platform must serve to avoid zero-sum competition, such as through subsidies or lower standards.

-

Coherent and complementary operations between development partners will help scale up private sector investment. The adoption of core standards can lower the private sector’s cost in working with a range of development partners.

-

Priority has to be given to linking up security, humanitarian and development efforts in states with features of fragility, working with UN agencies and other partners.

-

Cooperation within the country platforms would enable a rapid response in times of crisis.

-

Cooperation at the country level should also be supported by global platforms for the IFIs to collaborate on key thematic issues such as sustainable infrastructure.

-

Implement regional platforms to facilitate transformative cross-border infrastructure projects, that enable regional connectivity and open up new supply chains and markets.

-

-

Multiplying private capital by adopting system-wide approaches to risk insurance and securitization. Institutional investor participation in developing country infrastructure has so far been miniscule. The development of a standardized, large-scale asset class, that diversifies risk across the development finance system, will help mobilize this huge untapped pool of investments.

-

Reassessing regulatory capital and other prudential norms for the MDBs, as well as institutional investors in infrastructure, based on the evidence of their default experience.

-

Strengthening joint capacity to tackle the challenges of the global commons through tighter and more effective coordination mechanisms among the diverse organizations in each field, to enhance response capacity and to ensure adequate financing.

-

The IFIs must also mainstream activities in support of the global commons into their core country-based operations. We must likewise integrate trust fund activities with the MDBs’ strategies and operations, to avoid parallel structures that pose significant costs to efficiency and impact.

-

Investing in data and research to support sound, evidence-based policies. Basic data still falls short in many developing countries. These are public goods in their own right. The IMF and World Bank should work with UN agencies and RDBs to strengthen efforts in these areas.

-

Achieving stronger synergies with business alliances, NGOs and philanthropies so as to benefit from their on-the-ground perspectives, innovations and delivery capacity. The IFIs must work with governments to collaborate with and leverage on these actors more systematically, identifying key needs and providing space and co-funding where required so they can play their full roles.

Proposal 1: Re-focus on governance capacity and human capital, as foundations for a stronger investment climate.

Governance and human capital development have been at the core of the successful development stories of the last half century.

This agenda succeeds only when it is owned by countries themselves. However, the IFIs should refocus their efforts, individually and collectively, on assisting countries in strengthening governance capacity, spreading best practices more quickly, and spurring the adoption of new technologies that improve productivity and enable more inclusive access to education and healthcare.

Strengthened governance capacity is essential to mobilizing domestic financial resources and creating an attractive investment climate, both at the national and local levels, by:

-

Improving domestic tax administration and reducing leakages

-

Reducing corruption which is a major constraint on economic development

-

Developing the domestic financial system, particularly by deepening local currency capital markets.

-

Strengthening the rule of law and increasing regulatory certainty to provide confidence for long-term investors

The IFIs can also be effective in sensitizing governments to a critical unfinished task in human capital development: the need for equality of opportunity for all, regardless of gender, ethnicity and social backgrounds. They should also encourage governments to leverage on the initiatives of the non-official sector, including NGOs and philanthropies, and the private sector, to spread opportunities widely.

However, building governance capacity and developing human capital take time. Special attention must be paid to countries with significant elements of fragility,to help reformist governments to achieve progress in creating jobs and widening access to services, and thereby build public support for continuing reforms. There is otherwise a real risk of governance reforms being undermined by a lack of demonstrated success in improving welfare.

Proposal 2: Build effective country platforms to mobilize all development partners to unlock investments, and maximize their contributions as a group, including by convergence around core standards.

Country platforms, owned by governments, will enhance contributions from all development partners including the private sector. They can be transformational in their development impact:

-

Exploiting the complementarity among a country’s development partners – the IFIs, UN agencies, bilateral official agencies, and in some cases philanthropies and NGOs – hence taking advantage of their combined strength and knowledge.

-

Enabling development partners to provide more consistent and better coordinated support for policy and institutional reforms.

-

Scaling up private sector investment through coherent and complementary operations between development partners.

-

Facilitating adoption of common core standards to ensure sustained development impact and lower the cost of working with the range of partners.

-

Strengthening crisis response capacity as they provide a coordinating mechanism that can be utilized for immediate response.

Importantly, the platforms must not be a straitjacket on either the government or development partners:

-

To be effective, they must have strong government ownership, preserving the government’s flexibility to engage with partners with appropriate strength. The platforms should also be able to evolve differently across countries, depending in part on governments’ planning capacities.

-

However, country platforms also have the potential to help governments in planning through the life cycle of public assets, and to enhance coordination across agencies within government with Ministries of Finance usually playing a coordinating role

-

For development partners, transparency within the platform and convergence on core standards will encourage healthy competition around innovation, efficiency and speed to market and improve the investment climate.

The use of country platforms has so far been fragmented and selective. They have been mainly used in post-conflict reconstruction or at a sectoral level (see Annex 1 for an overview of existing forms). None yet combine the transparency, convergence around common development standards, and the standardized approaches needed to achieve a major step-up in private sector investment. Developing such country platforms will hence require a significant shift in the way the development community operates.

Effective country platforms require a high level of transparency, to ensure that all partners have access to and share relevant information. They will involve the partners adopting a set of agreed core standards to ensure sustainability, and to avoid competition of a zero-sum nature such as in subsidies. The adoption of common core standards will improve the ease with which the private sector can collaborate with different development partners (see Box 2).

Box 2: Core Standards

Core standards should aim at achieving coherence amongst the multiplicity of today’s actors in development finance, and enable them to focus on unlocking synergies in the system. It would also enable both governments and the private sector to work more effectively with different development partners and at lower cost.

This would involve the system agreeing to a set of five/six core development standards with appropriate sequencing for states with features of fragility. They could include:

-

Debt sustainability.

-

Environmental, social and governance standards.

-

Coherent pricing policies.

-

Local capacity building.

-

Procurement.

-

Transparency and anti-corruption.

Currently the IFIs broadly adhere on the principal components of the core standards. The development of and convergence towards core standards must be done in close collaboration with shareholders. With regard to certain standards (e.g. transparency and anti-corruption, debt sustainability and pricing policies) – convergence needs to be accelerated. In other areas, convergence should start with a broad equivalence approach, with agreement on principles and outcomes. This would allow for different approaches aimed at the same objective of protecting citizens today and in the future, and enable convergence over time.

Importantly, this effort to converge on a set of core standards should form the basis for bringing on board major bilateral lenders/development finance institutions (DFIs), as they have collectively become much larger players in development finance. The IFIs should collaborate with the International Development Finance Club (IDFC) and private sector entities in their ongoing work on standards. Cooperation among shareholders is critical in this regard.

Special consideration will need to be given to states with features of fragility as they will require a more customized approach to standards, tailored to their capacity, and with greater support for implementation.

Country platforms are often more effective when governments have the support of coordinating development partners. Selection of such coordinators should be based on practical considerations regarding the country’s development priority areas. To encourage wider ownership, the coordinator role should ideally be rotated on a regular basis.

Importantly too, the country platforms will ensure that the RDBs continue to play active roles based on their comparative strengths – especially their regional knowledge and relationships.

The coordination and coherence achieved on such platforms will help significantly scale up private sector investments. This would follow from coordination to strengthen government capacity in project selection, preparation and implementation; to build regulatory certainty; and to standardize contract documentation to enable the development of an infrastructure asset class. The platforms will also enable the IFIs themselves to integrate their project preparation facilities.

Country platforms will also be effective instruments in the case of crises. When they are functioning well, they will provide a coordinating mechanism to bring together the government and relevant IFIs, bilateral agencies, relevant UN agencies and other non-governmental actors at the onset of a crisis. They can provide organizing frameworks for humanitarian and other assistance as their operating principles will facilitate coordination and collaboration in real time.

Proposal 3: Implement regional platforms to facilitate transformational cross-border investments and connectivity.

Regional approaches help promote economic opportunity by allowing countries to overcome economic constraints resulting from geography such as lack of access to ports, lack of infrastructure connectivity especially in transport, and poor energy and water availability.

Regional projects are usually complex and expensive. They require the involvement of multiple countries and investors, coordination of difficult policy issues, and the resolution of complicated fiduciary, environmental and social arrangements. Establishing regional platforms, based on the same principles as country platforms, offers a good approach to accelerating the implementation of regional projects.

The regional platforms will allow for better collaboration and division of labor among the development partners operating in a region.28 They can also be used to accommodate small countries’ projects and programs, where individual country platforms may not be as viable.

Proposal 4: Reduce and diversify risk on a system-wide basis to mobilize significantly greater private investment, including portfolio-based infrastructure financing.

The IFIs’ efforts to help countries to strengthen government capacity (Proposal 1) and to derive synergies among development partners from well-functioning country and regional platforms (Proposals 2 and 3) are critical to strengthening the investment environment and project pipelines. However, to mobilize the vastly greater resources required to meet the coming development challenges, we must maximize the potential of capital markets and institutional investors Greater private financing in infrastructure must also be achieved without adding significantly to sovereign liabilities in countries where debt sustainability limits have been reached.

The G20 Hamburg Principles affirm the need for MDBs to crowd in private investors through credit enhancement and other means. Private investments in developing country infrastructure assets are today minimal. Investors’ risk perceptions of developing country infrastructure investment and expected returns are high. Risk must be reduced and managed so that returns and pricing sought by private capital can be brought down to a level that is viable and sustainable to developing countries.

There is significant scope for system-wide approaches to reduce, manage and diversify risk, to open the gates to private investment. These must involve:

-

Re-orienting MDBs’ business models to focus on risk mitigation.

-

Using system-wide political risk insurance and private reinsurance markets.

-

Developing a large and diversified asset class that enables institutional investors to deploy funds in developing country infrastructure.

Proposal 4a: Shift the basic business model of the MDBs from direct lending towards risk mitigation aimed at mobilizing private capital.

The MDBs, which have traditionally focused on lending, should shift to using their balance sheets to mitigate risk. MDBs (and bilateral development partners) have a unique ability to manage risks in developing countries through their multilateral ownership and ability to influence governments. They are hence well placed to provide credit enhancement (e.g. taking the first loss piece in a synthetic securitization structure) with institutional investors coming in to take a standardized senior debtexposure which can be priced lower to reflect the lower risk.

MDB credit enhancement can be a more efficient use of their capital than direct lending. Further, the benefit goes not to private investors – who receive a lower return commensurate with the lower risk they bear – but to the borrowing country through a lower financing cost.

Proposal 4b: Develop system-wide political risk insurance and expand use of private reinsurance markets.

Political risk insurance coverage is critical to draw international investors into many developing countries – through FDI and both debt and equity financing.

The MDBs should, as a system, leverage on MIGA as a global risk insurer in development finance. MIGA has significantly expanded its political risk insurance coverage provided to private investors in developing countries over the last five years. Its capacity has been boosted by utilizing the private reinsurance market. We can build on MIGA’s existing risk insurance capabilities to take on risk from the MDB system as a whole, and achieve the benefits of scale and a globally diversified portfolio. Collaboration among the MDBs and MIGA can take different forms, e.g. the MDBs connecting investors to MIGA; or MIGA reinsuring MDBs’ insurance/guarantee products. Greater use of private reinsurance markets will also allow the scaled-up use of political risk insurance.

MIGA should establish a joint advisory board involving participating MDBs to guide joint activities and oversee standards and pricing norms to support collaboration.

MIGA and the MDBs should significantly scale up current risk insurance operations by:

-

Standardizing contracts and processes. Standardized contracts will help facilitate scaling up the provision of risk insurance. They can aid in the creation of programmatic underwriting and pricing processes for insurance/reinsurance on a portfolio basis (instead of project-byproject review), thereby improving efficiency and speed to market and lowering costs.

Expanding the use of private re-insurance. A system-wide risk insurance platform would in the long term require a significant increase in the amount of risk ceded to private sector reinsurers so that MIGA and the MDBs can recycle their capital for more projects. A reinsurance panel could be selected and renewed through a competitive process. Reinsurance can be arranged on a portfolio basis using pre-agreed criteria.

Proposal 4c: Build a developing country infrastructure asset class with the scale and diversification needed to draw in institutional investors.

Institutional investors represent an enormous pool of potential investment that has so far evaded developing country infrastructure. With the exception of a few specialized players, they can only be drawn into developing country infrastructure if markets provide a large, simple and diversified asset for them to invest in. Thus far there have been promising but piecemeal efforts to structure investible products for private investment. The Argentine G20 Presidency has asked the Infrastructure Working Group to look at opportunities for mainstreaming this asset class.

We can only achieve scale by taking a system-wide approach: by pooling and standardizing investment from across the MDB system into securitized assets or fund structures that enable easier investor access. The IFC’s Managed Co-Lending Portfolio Program (MCPP) is an example of a loan portfolio from a single MDB that has successfully garnered private sector interest. Standardizing and pooling across the system will generate larger, more diversified loan portfolios that will significantly scale up institutional investor participation. Equally important, the pooling of diversified portfolios of MDB loans for private and institutional investment confers significant benefits upstream in the project cycle, by driving commercial discipline.

There is a significant amount of loans in the MDB system, infrastructure-related and others, that could be pooled for private and institutional investment. This could start with the US$200-300 billion of non-sovereign loans, sufficient for an asset class of reasonable scale. The eligible loan pool can be further widened to include commercial banks’ infrastructure loans, of which there are about US$200 billion issued annually. The growth of green bonds and green bond funds is another opportunity for MDBs and commercial banks to originate infrastructure loans that respond to the needs of institutional investors.

New sovereign loans can also be pooled for investment, which should ideally be done once the market is familiar with the asset class. This can be done by clean sales of loan portfolios to private and institutional investors which would not involve a transfer of preferred creditor status (see Annex 2 for more details).

Proposal 5: ‘Right-size’ capital requirements for MDBs and other infrastructure investors, given their default experience.

A set of prudential norms specific to and applied across all MDBs need to be established, based on their unique characteristics and default experience. Currently, the regulatory capital and liquidity standards and rating methodologies applied to MDBs are adapted from those developed for commercial banks and do not sufficiently reflect their distinctive shareholding structures, preferred creditor status and default experience. The different rating agencies also adopt varying methodologies for the MDBs. As a consequence, the MDBs each have different adaptations and capital and liquidity buffers. The larger the buffers, the more constrained the MDBs will be in their financial capacity.

In a similar way, the regulatory capital treatment for infrastructure investment applied to banks and institutional investors such as insurers do not differentiate such investments from generic corporate debt. This has acted as a disincentive to investors to take on infrastructure investments. Evidence however shows that long-term investments in developing country infrastructure have a better default experience than corporate debt. The case for carving infrastructure investment out as a separate asset class distinct from corporate debt in the capital treatment for insurers and certain other institutional investors should be revisited based on the evidence.

Proposal 5a: Establish tailor-made capital and liquidity frameworks for the MDBs.

MDBs should collectively approach the Basel Committee to seek guidance on the regulatory capital and liquidity standards for MDBs, considering their unique operating models. An independent review by the Basel Committee and the development of a tailor-made regulatory framework would promote the adoption of harmonized capital and liquidity approaches across the system, and provide a basis for rating agencies to also review their rating methodologies for MDBs. The aim is for MDBs and rating agencies to more accurately quantify the risk taken on by the MDBs and so determine the appropriate capital and liquidity requirements. Should some balance sheet capacity be freed up, this can be deployed to take on risk. The issues that could be addressed include:

-

Taking into account the key elements that differentiate MDB operating models from commercial banks, including the recognition of preferred creditor treatment, callable capital and concentration risk

-

Actual default experience across the MDBs.

-

The treatment of credit guarantees/enhancement and insurance as compared to more traditional loan instruments should be risk and evidence-based.

The MDBs also currently do not have access to any support facility in case of extreme liquidity stress and are treated by the rating agencies as such. As a result, they are holding more liquidity (excessive self-insurance) and/or pay a higher cost of capital (the rating agencies treat the MDBs as financial institutions without access to liquidity backstops) than needed if the MDBs were viewed as a system.36 As part of their approach to the Basel Committee on the establishment of a regulatory framework for the MDBs, they should also seek guidance on the appropriateness of a liquidity back-stop.

From time to time, the system as a whole should be stress-tested with a view to strengthening its overall resilience, and better understanding resource needs both in normal times and in crisis

Proposal 5b: Review the regulatory treatment of infrastructure investment by institutional investors.

Institutional investors from both developed and emerging markets are constrained by regulatory standards from investing in infrastructure. Home country institutional investors can bring to bear superior contextual knowledge and a strong alignment in investment objectives (e.g. in a requirement for local currency investment), if regulation also facilitates and recognizes their potential valueadd to the infrastructure development ecosystem. Using an evidence-based approach to review regulations may identify opportunities for incentivizing long-term investment.

There is scope to review the regulatory treatment of infrastructure debt based on the evidence, and to consider it as a distinct asset class from corporate debt with its own differentiated risk profile. There is also scope for risks to be differentiated between the construction and operation phases, with the latter posing a lower level of risk.

Proposal 6: Strengthen joint capacity to tackle the challenges of the global commons.

The global commons face a wide range of challenges, including environmental threats related to climate change, degradation of ecosystems, loss of biodiversity, water scarcity and threats to oceans and specific health-related threats from pandemics and the rapid spread of antimicrobial resistance. The poor are often more exposed and invariably more vulnerable. Another related challenge involves forced displacement of people because of conflict, natural disasters and lack of security. These are challenges for all countries, but the international community has a critical role to play both in supporting developing countries in protecting the global commons and through their own national actions.

Total infrastructure capital round the world will double in the next 15 years. How that investment takes place will have a profound influence on the global commons. The IFIs have an essential and urgent role to play in ensuring the quality and sustainability of that investment.

These challenges all span national borders and require international action to provide the public goods (transnational and local) and relevant policies and investments to respond to these threats with greater urgency, scale, coherence and impact. The appropriate responses for the different challenges differ greatly in scale and scope as well as in the complexity and speed of delivery.

The differences across the global commons also have important implications for how efforts should be coordinated, and for the allocation of responsibilities across institutions As the system shapes the response, coordination must look at the scope of the spillovers and the nature of public goods, policies and investments needed to respond.

While these challenges to the global commons are very real, technology has also been advancing at a rapid rate. There are huge opportunities to make progress on a broad range of issues critical to quality of life and sustainable growth. Environmental limits create imperatives for change, but they also spur creative thinking on how to design livable cities with citizens living healthier lives and working in high-quality sustainable jobs. IFIs have a particular responsibility in spreading innovation. Innovation in sustainable development is already generating growth opportunities.

Proposal 6a: Integrate activities in support of the global commons into the IFIs’ core programs, and coordinate them within country platforms (Proposal 2).

IFIs have a critical role to play, in the context of country-based programs, in setting global standards and developing market-based approaches that would crowd in the private sector into action on the global commons. The World Bank has exercised leadership working in partnership with the private sector through, for example, the Carbon Price Leadership Coalition; and the RDBs have taken similar initiative in specific areas. The IFIs should encourage the adoption of standards regarding the disclosure of risks associated with the challenges to the global commons. The 2017 recommendations of the FSB-initiated Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) have begun to be implemented by investors and companies, supported – and in some cases required – by their governments.

IFIs should also help countries incorporate their programs for the global commons into their growth strategies and investment plans and assist them in adopting a consistent approach across the government.

Proposal 6b: Create global platforms with the UN guardian agency and the World Bank coordinating and leveraging on the key players in each of the commons.

An effective international response to the challenges and opportunities of the global commons requires strong action within and across countries, and across the UN agencies, IFIs and other relevant bodies including philanthropies and the private sector. The current scale of activities falls far short of what is needed given the urgency and magnitude of the challenges. The designated UN guardian institution for each of the commons and the World Bank, which has the broadest reach among the MDBs, should be responsible for identifying gaps in the global response, such as climate change adaptation, and coordinating and leveraging on the key players. For specific commons there will be RDBs and other stakeholders with significant capabilities that should play key roles.

The current global efforts to tackle the challenges of the global commons have significant degrees of duplication between agencies, overcrowding in certain fields and gaps in others. We need clearly delineated roles to strengthen impact.

While the system must be capable of responding in a decentralized fashion, it must be more tightly coordinated to leverage the joint capacity of the IFIs, UN agencies and other development partners. The UN agencies have a normative function in most areas, defining goals, setting standards and providing political legitimacy. They are also in many instances first responders in emergencies and crises. The IFIs play different key roles, based on their comparative advantage in policy advice and derisking, mobilizing finance, building resilience and strengthening countries’ implementation capacity. The private sector has a crucial role to play and its collaboration with the MDB system should be strengthened. The philanthropies, often working with the private sector and NGOS, are also a source of important innovation, experimentation and establishing systems for measuring impact.

The alignment of responsibilities of each institution should be based on its comparative advantage in each stage of the ‘value-chain’ of activities: investments in R&D and innovation, mobilization of finance, prevention, resilience and crisis response. The illustrations below indicate the potential of collaboration leading to greater impact.

-

R&D and innovation: The IFIs together with the specialized UN agencies, should collaborate to collect data and undertake the analytical work necessary to develop early warning indicators, and prevention and resilience plans. The philanthropies with more risk absorption capacity play an important role in funding R&D and innovation.

-

In response to the West African Ebola virus epidemic (2013-2016), Wellcome Trust played an important role in the development of vaccines – a risky activity which is difficult for MDBs to engage in.

-

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), in partnership with the AfDB and ADB, is funding efforts to scale up financially and environmentally sustainable sanitation services for urban poor communities. The BMGF is providing grant funding to support R&D in innovative technologies, and AfDB and ADB plan to scale up deployment of those technologies that prove viable.

-

MDBs can contribute to scaling up innovations which have passed the initial high-risk development stage.

-

Mobilizing finance: The MDBs are best positioned to crowd in private resources into the global commons. In addition to their regular financing, MDBs should develop contingent public finance facilities and system-wide insurance instruments which are key to fast disbursement and launching support operations. Important examples are the World Bank Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility, supported by bilateral aid agencies and the WHO; and the Africa Risk Capacity, a weather-based insurance mechanism to enable food security and involving partnership between the African Union (AU), bilaterals and the World Bank. There is substantial scope to scale up such initiatives.

-

Prevention and resilience: There is significant untapped potential in the combined data and knowledge of the IFIs that can be used to develop early warning indicators and design appropriate prevention and resilience programs. IFIs are also uniquely positioned to ensure that their programs and projects embed appropriate prevention, preparedness, and resilience mechanisms, including helping the most vulnerable adapt to climate change, and early and effective response to pandemics or famine. A good example is the IDB’s Emerging and Sustainable Cities Program which aims at strengthening resilience by combining environmental, urban and fiscal sustainability and governance, particularly in relation to sustainable infrastructure.

-

Crisis response: Intrinsic to effective crisis response is tight and speedy coordination between the IFIs, UN agencies and other development partners. The World Bank’s Global Crisis Response Platform is an important element of such an integrated approach. The WHO-led, Gavi-supported, effort to combat the recent outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is an example of how an integrated approach can effectively staunch a dangerous pandemic outbreak.

The evolving architecture for global health to combat pandemics, and anti-microbial resistance (AMR), with the WHO playing a normative role and performing a coordinating function, provides a good model for how a global platform could be structured for each of the commons (see Annex 3).

A new cooperative international order must also enable mobilization of flexible coalitions of countries and institutions around specific global or regional commons. One such initiative is the UN-World Bank High Level Panel on Water. The Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 was launched on this common undertaking and is an example of how multilateral organizations, bilateral partners and national authorities can join forces and avoid fragmented efforts for greater long term impact. The Global Commission on Adaptation, soon to be established, is another example of how a coalition of partners can come together on a critical challenge.

Proposal 7: Integrate trust fund activities into MDBs’ core operations to avoid fragmentation.

MDBs currently operate with considerable resources outside of their balance sheets, mostly in the form of trust funds.44 These funds represent donors or coalitions of donors that are willing to provide additional financial support to achieve specific development objectives. However, the large number of trust funds and their alternative governance structures are fragmenting MDB activities, driving a misalignment between trust-funded activities and the MDBs’ strategic objectives, and engendering administrative and operational inefficiencies. Moreover, trust fund activities can complicate and reduce country-ownership as they are generally earmarked for specific purposes and are non-fungible.

Some trust funds are achieving results in important and difficult areas, especially in situations of fragility. For example:

-

The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery- a global partnership of 400 partners – has provided just-in-time assistance to 20 countries vulnerable to climate-related hazards and helped them integrate climate resilience measures in their development strategies and programs during FY17.

-

The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund - a partnership of 34 donors – channels 50 percent of all development expenditures in Afghanistan and has benefited 9.3 million people by providing access to schools and health clinics in thousands of villages across the country.

However, the MDBs must work with shareholders to ensure that trust funds do not create parallel structures, at significant cost to the efficiency and effectiveness of countries’ programs and MDBs’ operations.

There are some examples of approaches that integrate additional resources with MDBs’ core operations:

-

The Global Concessional Financing Facility, which is part of the Global Crisis Response Platform, blends donor grant resources with World Bank non-concessional IBRD resources to provide support to refugee populations in Jordan and Lebanon.

-

The International Finance Facility for Education (IFFEd) is a new initiative targeted at supplementing MDB financing for lower-middle income countries as they lose access to concessional financing.

Proposal 8: Plug shortfalls in data and research that hamper effective policymaking, especially in developing countries.

There are major deficiencies in basic social, economic and environmental data, especially in developing countries. We must address these deficiencies in order to design and implement effective national programs for inclusive growth and human capital development.

The IFIs have a unique and globally important role to play in the generation, analysis and dissemination of data (including big data) and policy-relevant research. These are true public goods that are critical to understanding and tackling global challenges, fostering sound, evidence-based approaches to economic development and meeting the SDGs. The IMF and the World Bank are ideally placed to undertake these roles, and to work closely with the UN agencies and the RDBs that play similar roles in areas related to their specific mandates.

With the production of data and research come a responsibility to share. The IFIs have often played a leading role in promoting transparency, but they must go further, particularly in sharing information with each other, with governments, and, wherever appropriate the public at large.

Proposal 9: Leverage more systematically on the ideas and operating networks of business alliances, NGOs and philanthropies.

There is significant scope to leverage on business alliances, NGOs and philanthropies to improve development impact. They contribute new ideas, grassroots perspectives, and can mobilize expertise and resources that complement those available to the IFIs. They can also enhance delivery capacity in situations where the IFIs have difficulty engaging, such as in situations of fragility and conflict.

There are numerous examples of the value created by such actors. For example:

-

Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) is a grassroots organization and movement of poor, self-employed women workers. It has grown from 30,000 to 1.9 million women as members in two decades. SEWA has worked to empower women, organized health services for the poor and been active in micro-finance. It has served as a model for unleashing technology to spark innovation and enterprise at the grassroots level.

-

BRAC is a non-governmental organization to help the poor originally in Bangladesh but now with activities around the world. Through innovative, evidence-based approaches to development it has affected the lives of millions and changed both thinking and practice around development.

-

The campaign for debt relief for heavily indebted developing countries around the turn of the millennium provides a powerful example of how a civil society coalition, Make Poverty History, built momentum for the IMF, World Bank and ADF’s HIPC initiative that made important contributions to achieving education and health objectives.

The IFIs have begun working more with civil society and philanthropic actors. The IFIs can leverage more systematically on their efforts and capabilities, identify key needs and gaps, connect them with official initiatives, and provide space and co-funding for these actors to play their full roles. A key role of the IFIs in this context is to take good ideas to scale.